A day of two halves

This morning my friend, Fatma, met me at Queen’s Park station in London to take me to the second-hand bookshop she and her partner opened two and a half years ago, which I had never visited. What a gem! As we came up to it I saw someone at a table reading a book from the baskets Fatma had left outside. She greeted him by name, unlocked, took down the notice saying ‘Back at 10.30’ and we all went into the tiny book-lined space where she made us coffee.

Fatma and I talked, another two customers talked, then she introduced me to a new arrival, J. A poet, I suspect. We chatted about Gerard Manley-Hopkins, ancient Greek, etymology, Malevich and whether or not photography is art. Cordial goodbyes, with an invitation to come to the monthly poetry group in the shop, and in came S, who works in the greeting card industry. We chatted about how cards keep many shops going, whether offensive cards are OK and the shop’s film nights. Then R came in, greeted S and Fatma, introduced himself to me, and the conversation switched to politics, the 70s, hypocritical alliances, Sinn Féin and what will happen to that border.

A bunch of customers as eclectic as the book stock and Fatma seems to know them all.

Then I was meeting my mum at the National Theatre to see Salomé, by the writer and director, Yaël Farber. I’ve loved everything I’ve seen of hers but a couple of days ago I checked to see how the Guardian rated it. One star, for turgid writing barely redeemed by the ‘luscious design’. Oh dear. We wondered whether we should just stay outside in the sunshine but agreed to decide for ourselves.

The storytelling was complex, mythic and hard to unravel. The interpretation was political: about the oppressive, autocratic power of Rome (the US?, Russia?) over Judea (Syria?). Rome was bringing aqueducts and roads to be paid for either by taxation on locals who had no interest in such things or – the imperial power having neither understanding of nor concern about religious sensibilities – by an impious raiding of the temple’s sacred coffers.

In this telling the colonial power was desperate for the imprisoned John the Baptist (who spoke only Syrian Arabic on stage) to be kept alive, since martyrdom would increase his following among the resistors and perhaps unite their factions. Salome’s calling for his head was not a sexualised caprice but a political act to turn him into that martyr.

The parallels with contemporary politics are fairly obvious even if I’ve misunderstood some of the detail but the play was also, with Herod’s (implied) rape of Salomé, about the oppression of women. I was initially irritated by Salomé removing her ‘seven veils’ full-frontal (Brazilian and all) at the very front of the stage, but Yaël Farber isn’t stupid. She was making her audience complicit in oppression.

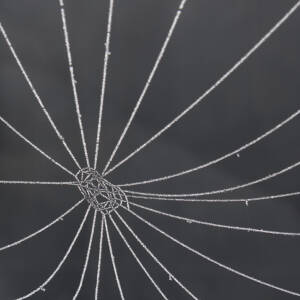

And yes the staging was luscious: curtains of fine sand falling from above; a tableau of The Last Supper; a ladder to the heavens, perhaps with an angel (Salomé); arcs of water-drops caught in the light; huge swathes of rich fabric to symbolise the dance.

More than one star.

Comments

Sign in or get an account to comment.