Ladybirds in ITA

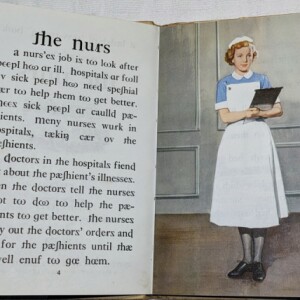

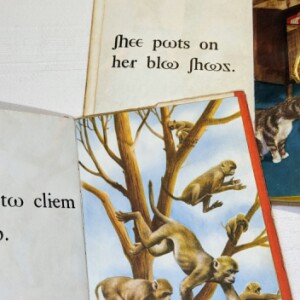

My big sort out of my upstairs work room continues. Among a box of books from my parents' loft are about twenty old Ladybird books, including some of the beautifully illustrated nature ones, which I want to keep. Most can go though - they were printed in huge numbers and mine are not in great condition, often bought for pennies at church bazaars, and will not be worth much, but people collect them so it's probably worth listing them as a job lot on ebay. However, amongst the pile were five books printed in ITA, the Initial Teaching Alphabet in use in my primary school when I started school in 1965. It was devised as a means of making the vagaries of English spelling less daunting, by using a distinct, phonetically based letter shape for each sound in English. As well as the familiar letters of the alphabet, each ascribed to one specific sound, it created new, and I think rather elegant symbols by combining letters. This means there is a single symbol for the sound normally written as "sh"; there are two versions of "th" for the hard and soft pronunciations (in the and thin, for example). Vowel sounds are carefully classified, with distinct symbols, for example, for "oo" (zoo) and "uh" (book); others can be identified on the pages I have photographed. It was all very clear and logical and I had no difficulty with it and quickly became a fluent reader in this new system, although (or perhaps because) I was already close to reading simple books in standard English when I started school. It was a delight to rediscover the books: The Zoo was "from Mummy and Daddy, May 1965", my fifth birthday and the month after I started school, and Puppies and Kittens claimed to be from my younger brothers. Somewhere among the papers my mum retrieved when clearing the house of the aunt who had brought her up (and thus effectively my grandmother), there were a handful of thank you letters and holiday postcards written by me to Aunty Maggie in careful ITA handwriting between the ages of five and about seven.

My experience of ITA, with an enthusiastic young teacher, probably reflected the idealism with which it was introduced. I grasped it quickly and was soon reading more substantial books. I can't remember when I moved onto standard English or to what extent I used both in parallel, but I quickly became a voracious reader, borrowing the maximum number of library books every week and begging my father to check out extra ones on his ticket; and in due course I became a linguist with a curiosity for spelling systems and the way languages work, and a language teacher committed to trying to make sense of the sound-spelling link in the languages I taught, so that children could decipher the French and Spanish they heard, pronounce the words they saw and, in due course, learn to make an educated guess at the spelling of new words they heard. ITA was subsequently much criticised, for failing to provide a transition route to standard orthography, for creating confusion and for limiting the potential of the opportunities the world around us offers to exploit the excitement of young readers, who were surrounded by signs and written material in a language which looked quite different to the one they were learning at school. Many children, including my brother, subsequently blamed early exposure to ITA for a lifetime of difficulty with spelling. By the late sixties the experiment had largely fizzled out, but despite the legitimate objections, I still have an affection for the system, its visual characteristics, and what it was trying to achieve.

I don't know how many ITA Ladybird books are still around; there is little reference to them on Ladybird websites, so I have no clear idea whether my rather tatty copies are of any value. Having rediscovered them, I would like to hold onto them for a bit longer, along with the many other objects I can't bring myself to throw away. This kind of clearing up is interesting and revealing, but it's very hard to make much progress!

Comments

Sign in or get an account to comment.